As I’ve indicated in the previous installments of Vintage Whine in Copper #75 and #76, the story of Sherman Fairchild goes far beyond the realm of audio, and at some point really should be detailed in a full-fledged biography—the range and extent of his interests and achievements beggars belief. Fairchild’s ventures in pro and consumer audio alone deserve far more space than I’m able to devote to them here.

This installment, we’re going to focus on Fairchild gear as it applied to records—both cutting discs and playing them back. But first, a caveat: if one were to explore the vintage audio products made by Marantz or McIntosh, or even Fisher or Scott, those are well-documented. There’s considerable reference material available on those products, and in some cases there are company histories available and even restorers who specialize in bringing classic models from those brands back to life.

As far as I can tell at this point of my research into Fairchild’s audio products—none of that exists for the brand. And so, it’s entirely likely that errors will be made in these stories, in spite of my best efforts to verify every factoid.

Keeping that in mind—onward!

Fairchild gear was involved in recording and cutting some of the most-revered records ever pressed. Last issue we showed cutting engineer George Piros at the controls of a Fairchild 523 cutting lathe, part of a pretty complete Fairchild suite at Reeves Sound Studios. According to our friend Tom Fine, his father Bob Fine worked at Reeves Studios in the late 1940’s, alongside Piros. Tom adds, “My father’s first studio, in Rockland County, had a Fairchild cutting lathe with a Miller Cutterhead. And of course the early Mercury Living Presence recordings were done on Fairchild tape machines….MLP wasn’t recorded in stereo until very late 1955, so everything from 1951-1955 was mono, and recorded on Fairchilds.”

As we’ve previously noted, Fairchild never did anything halfway, or on the cheap; the gear was built to be the best available, and was built to last. That 523’s cost of just under $3,000 was about the price of a new 1948 Cadillac, and today would equal about $32,000.

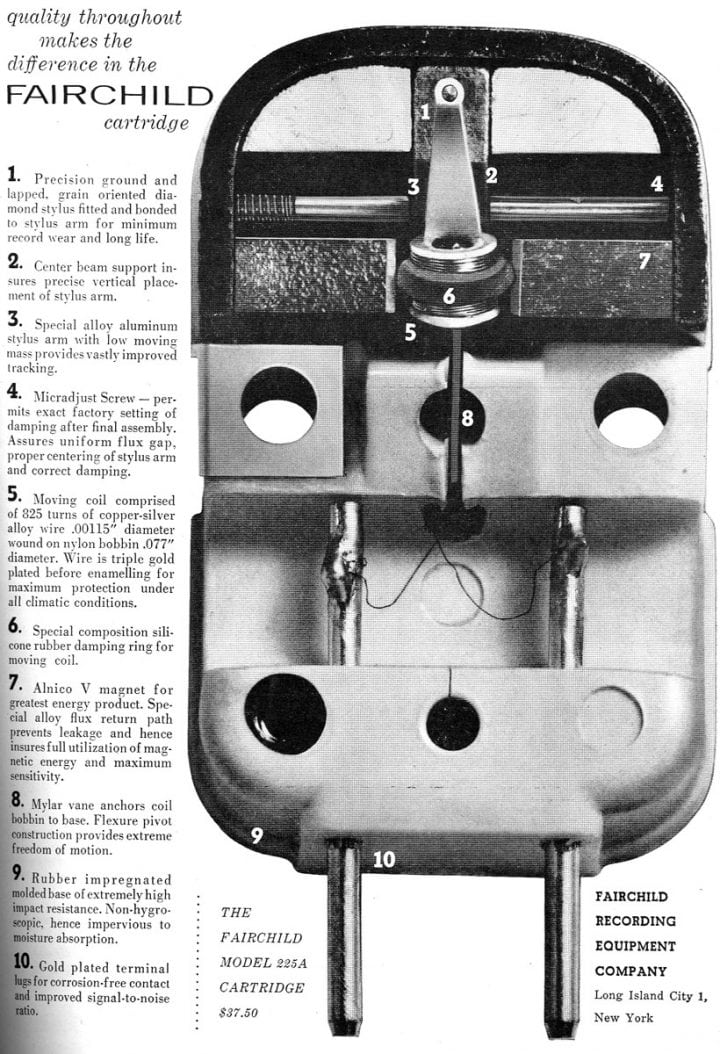

Entering the ’50s, Fairchild was a leader in record playback. We’ve previously written about the Model 225 moving coil cartridge, which is still sought by collectors and retrophiles. It may have been a compact, lightweight device, but it appeared particularly robust—especially in comparison to many of today’s tiny megabuck cartridges.

Entering the ’50s, Fairchild was a leader in record playback. We’ve previously written about the Model 225 moving coil cartridge, which is still sought by collectors and retrophiles. It may have been a compact, lightweight device, but it appeared particularly robust—especially in comparison to many of today’s tiny megabuck cartridges.

Not to keep harping on prices, but even that seemingly modest $37.50 in 1955 equals $350 today—of course, many moving coil cartridges today are ten or twenty times that. Or more.

In 1958, well-known audio engineer/man about town Bert Whyte wrote in Radio & TV News about the first Stereo record releases—and the new gear needed to play them. Of the Fairchild stereo playback gear, Whyte wrote “The arm used is the large studio turret head type which is found in many broadcasting stations. The cartridge is a novel design, utilizing two moving coils to pick up the ’45-45′ groove modulations of the Westrex system…the Fairchild stereo cartridge is at present quite a bit larger than its conventional 225 units [shown above] and for this reason the large studio arm is used….the present arm and cartridge works very well and it is actually available to those affluent people who can afford the rather breathtaking 250 dollar price tag. But then, there are always those who want to be ‘fustest with the mostest’.”

And yes… $250 in 1958? $2,200 today. Compared to many moving coil cartridges—a bargain!

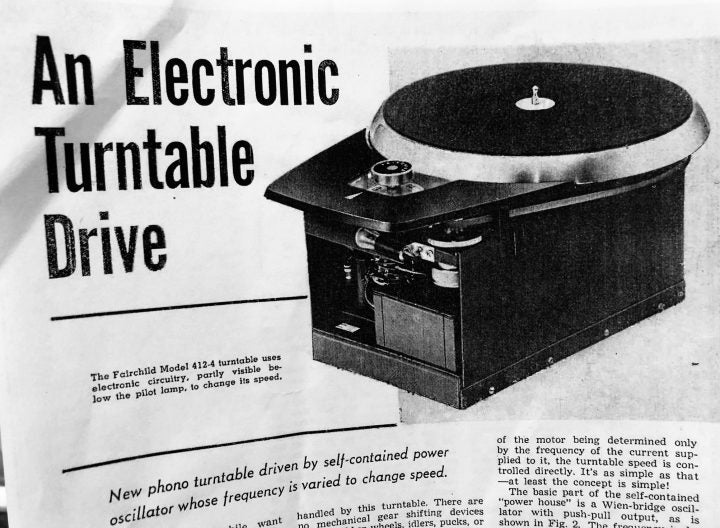

The most-legendary piece of Fairchild phono playback gear is the 412-4 turntable. In 1957 Radio & TV News found the new table worthy of a four-page feature upon its introduction. Typically for Fairchild, the table was built like a piece of industrial machinery: the chassis was heavyweight steel, the hysteresis-synchronous motor was suspended by spherical vibration mounts, drive was by two belts and an intermediate pulley for maximum decoupling, the main bearing was rifle-drilled Babbitt, the platter was a massive aluminum casting—well, you get the idea. But the really big news of the 412-4 was that platter speed was set and changed was not mechanical, but purely electronic, effected by an oscillator that changed the frequency of the current to the motor. In addition, the table could run on a.c. inputs from 85 to 135 volts, or on 50, 60, or 400 cycles—or from a battery supply!—all accomplished without any adjustments. Playing speeds were 16 2/3, 33 1/3, 45, and 78.26, adjustable plus or minus 5%.

0 comments