Written by Lawrence Schenbeck

It’s been a while since we featured any

oratorios in this column. Maybe the last time was 2016, when the subject was Craig Hella Johnson’s

Considering Matthew Shepard (

Harmonia Mundi HMU 807638/39). Yet oratorio continues to be one of the most viable genres in the classical tradition. A hybrid form itself—opera-minus-costumes-plus-church-music—it’s lately been subjected to further hybridization: for example, Britten’s

War Requiem (1962)

, which combines the Latin liturgy with a soldier’s poems from the Great War. Thus, vivid first-person narratives (sung by palpable

characters, if you will) perch alongside the words of the Catholic Mass for the Dead; the texts inform each other.

I like the way online

Britannica reminds us that “

oratorio derives from the

oratory of the Roman church in which, in the mid-16th century, St. Philip Neri instituted

moral musical entertainments.”

That explains Leonard Bernstein’s Mass (1971), the Latin of which was, like the War Requiem, enhanced with added texts—in this case by Stephen Schwartz (of Wicked fame) and the composer himself. Through those additions, the moral component of Bernstein’s entertainment received extra emphasis. That included not only his characters’ crises of faith but also critiques of the Vietnam war and certain elected officials; Nixon refused to attend.

Mass was billed as a “theatre piece,” but today many older pieces are being successfully retrofitted for the stage. Handel (1658–1759) helped us by actually writing theatrical directions in the scores for some of his oratorios; Semele and Saul practically cry out for theatrical presentation. And why not? As words-and-music, not much separates something like John Adams’s multi-textual, multimedia “nativity oratorio” El Niño (2000) from the Christmas Oratorio by J. S. Bach (1658–1750). Or from Bach’s Matthew Passion, recently staged for the Berlin Philharmonic by Adams collaborator Peter Sellars, who has also staged at least one Handel oratorio, Theodora.

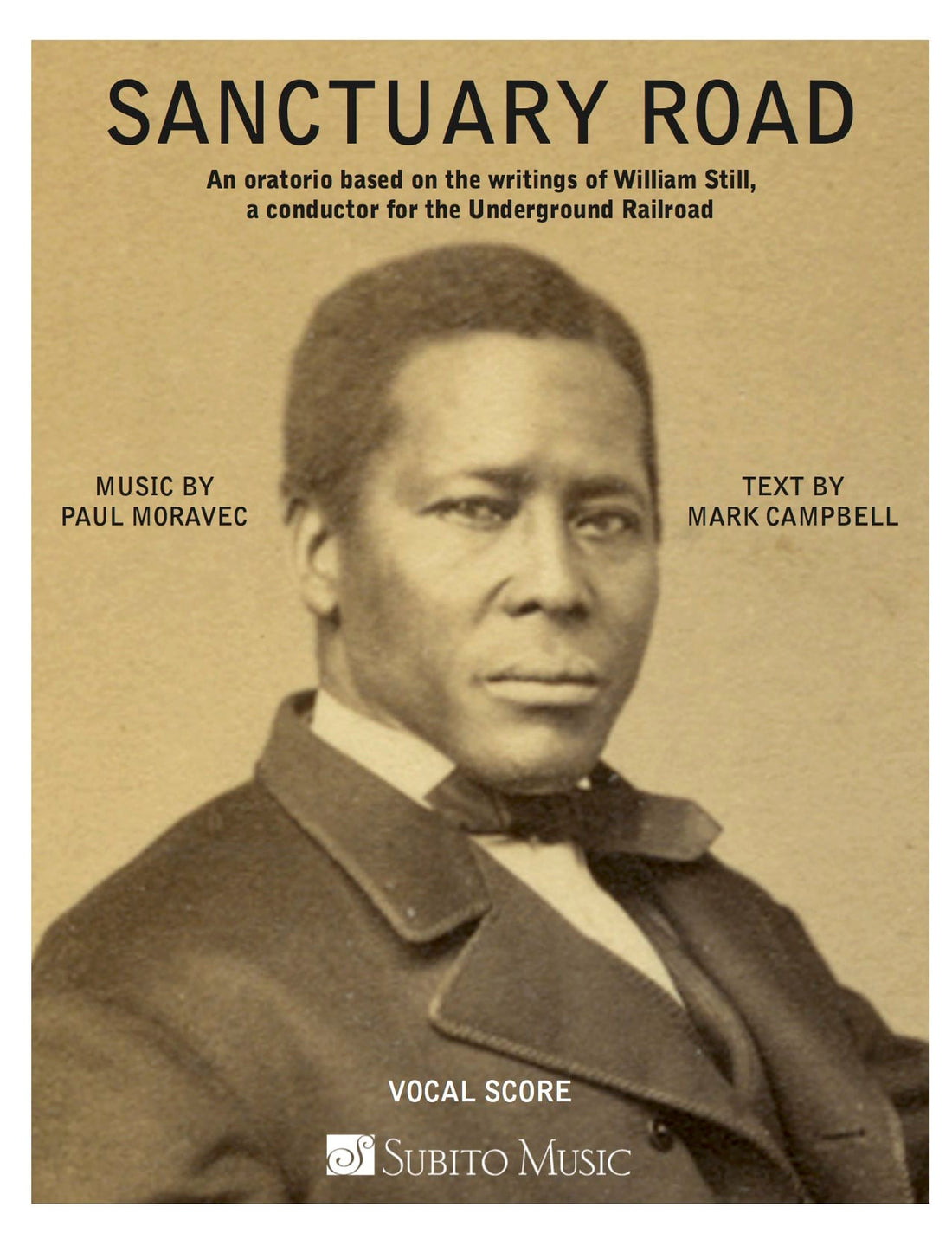

All of which brings us to today’s topic: Sanctuary Road (2018), music by Paul Moravec (b. 1957), libretto by Mark Campbell (b. 1953). A Naxos recording of the premiere was released in January, gaining a well-earned spot on Billboard’s Top Ten Classical chart for several weeks. Well-performed and well-engineered, it’s a “live at Carnegie Hall” keepsake worth hearing and owning.

Librettist Mark Campbell has become known as the go-to guy for great opera books. He scripted Silent Night (2012; music by Kevin Puts), The Shining (2015; music by Moravec), and The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs (2017; music by Mason Bates). Plus 35 others! Some have won high honors, like a Pulitzer Prize or a Grammy; many have received multiple productions from different companies.

Campbell’s collaboration with composer Paul Moravec, himself a Pulitzer awardee, is ongoing. Besides their work on Sanctuary Road and The Shining, they are polishing another oratorio, A Nation of Others, for its premiere in May by the Oratorio Society of New York, which also participated in the creation of Sanctuary Road. (Disclosure: I have written program notes for several OSNY performances, and I am currently working with composer and librettist to assemble notes for the May 2020 premiere of A Nation.)

Sanctuary Road owes its birth to a member of the Oratorio Society who had grown up in segregated Kentucky and wondered whether the group could find a way to focus light on America’s troubled racial past. She had sung in Moravec’s The Blizzard Voices (2008), first of what he now calls his “American historical oratorios.” Her experience with that work, which depicted stories from a legendary snowstorm that devastated the Great Plains in 1888, inspired her to commission a new oratorio. Moravec and Campbell proposed a project based on William Still’s The Underground Railroad Records, published in 1872. Still had served as a “conductor” on the Railroad before the Civil War, keeping meticulous records of his passengers’ experience. Eventually he helped some 800 fugitive slaves escape to the North; their stories would form the textual basis for the oratorio. Campbell came up with a title that linked the dream of safe passage to a better land with a term resonant once again in American life.

Five soloists do the storytelling. Bass-baritone Dashon Burton portrays Still himself, interviewing Railroad passengers and emphasizing the significance of the written record:

His narration is woven around a handful of individual stories that provide the most arresting drama in the fifty-minute work. My personal favorite was the tale told by fugitive Ellen Craft, sung here by mezzo-soprano Raehann Bryce-Davis, a 2018 winner of the George London Award. Craft disguises herself as an elderly, ailing white gentleman in order to catch a train to Philadelphia and freedom. In the next car, her “valet” accompanies her on this journey. But, as she explains, he’s not really her valet. As she lets us in on her secret, the music, skittish at first, gradually and effortlessly moves closer to Dvořák or Stephen Foster:

They see me as a sick, white gentleman,

Who has his own valet—a black man who sits with the other slaves,

In the other car.

But he’s not my valet . . .

He’s the man I will marry,

The man I will marry in Philadelphia.

He’s in a different car.

But we’re on the same train,

Humming along like a hymn,

All the way to Philadelphia,

To Philadelphia.

Moravec also deftly captures the grim humor in Henry “Box” Brown’s story, sung by Malcolm Merriweather. To escape, Brown had himself nailed into a crate and shipped from Richmond to Philadelphia:

They can’t seem to read.

The don’t seem to know.

The crate I’m in,

It says:

“THIS SIDE UP WITH CARE”

In big, big letters.

To clarify:

“This Side Up” is above me,

Not below.

Been on a cart,

On a train,

On a steamer,

And on a train again. . . .

My brain may burst from being

Upside down.

And my eyeballs may explode.

But it’s worth every second,

Every second of those twenty-six hours. . . .

The chorus doesn’t get to show off quite as much, but they do a terrific job when called upon, as in the triumphant hymn that ends the work. There’s more complicated choral singing in a movement titled “Reward!”, where the choristers impersonate a raging collection of slaveowners, offering money for the apprehension of “property” who have somehow gotten away. More than anything, the music makes it clear that fugitives came in all shapes, sizes, ages, genders, and skill sets, united only by their desire for freedom.

It's a compelling set of stories, heightened by the skills of the composer, librettist, and performers. Ably recorded and mastered, too, by Carnegie Hall's Leszek Wojcik and Joseph Branciforte. If you’re in New York City in early November (and if our current national dilemma has abated), you may be able to catch its sequel, A Nation of Others, which chronicles the American immigrant experience. Like Sanctuary Road, it will be conducted by the Oratorio Society’s magisterial music director Kent Tritle.

Should be a night to remember!

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ImDoW6P_AHM&list=OLAK5uy_l09IUrV77NMF4ZenSFLHJmiblmQ1gdvj4

(The above link provides all of Sanctuary Road plus a ten-minute “making of” audio featurette hosted by WQXR’s Terrance McKnight. You may want to have a libretto handy, which you can get right here.)