The transport control buttons and counter on a Studer A80. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.

The transport control buttons and counter on a Studer A80. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.Since then, magnetic tape recorders have ranged from miniature machines made for James Bond-esque espionage operations, to massive industrial tape duplicators. Their applications have included recording music and voice, logging the output of radio stations, recording radio commercials and programs to be broadcast at a later time, storing computer software and data, industrial process logging, storing and providing automation signals for industrial machinery, logging aircraft flight data, storing video signals, and more. [I once owned an Oberheim OB-8 synthesizer that used cassette tape as a backup – Ed.]

Out of the vast number of makes and models of tape machines intended for audio, very few were truly purebred professional machines, designed with the professional audio facility in mind. Out of these few, several were rather crude and primitive, especially in the early days. As the technology developed and matured, more refined tape machines began to appear. Their performance improved and the machines became more rugged and reliable.

The peak, or Golden Age, was reached in the 1970s, when some of the finest tape machines ever made were introduced. They were big. They were heavy. They were reliable workhorses. They sounded good. They were used in the recording of almost every major album of this era in your collection. They often cost more than the buildings they were housed in.

Sadly, the peak did not last long.

While the designs of the Golden Age of tape machines were clearly led by talented engineers, the models that followed in later years were primarily led by economic considerations, aimed at an ever more price-conscious market, which was also starting to develop a fear of screwdrivers. The later machines probably sold better, but they certainly didn’t sound better. They didn’t last longer either and their mechanical transports left a lot to be desired.

In this series, I’m going to be taking you along for a ride to discover the best of the best, the crème de la crème of tape machines, the true giants of tape.

Ladies and gentlemen, please fasten your seat belt and let us embark on a little time travel:

The Studer A80

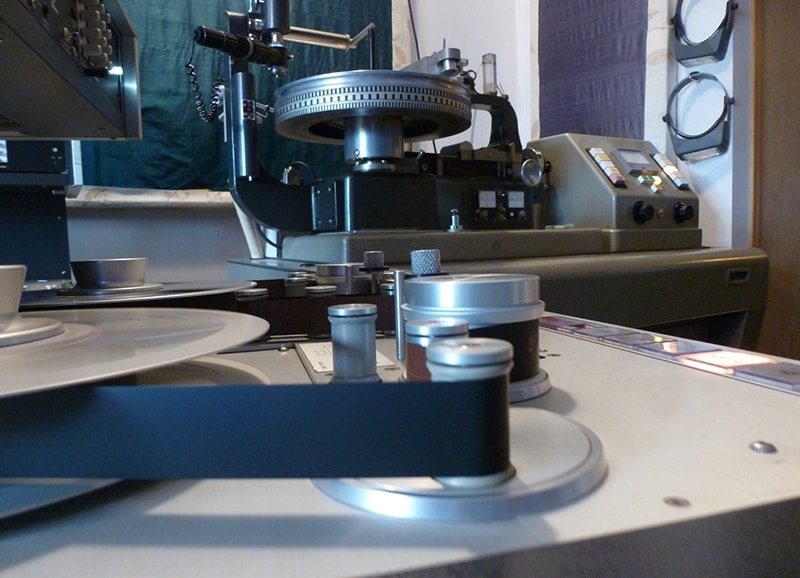

A Studer A80 spinning tape. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.

A Studer A80 spinning tape. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.

Introduced in 1970, the Studer A80 was to become one of the most popular tape machines on both sides of the Atlantic.

Manufactured in Switzerland by a company already long established in the field, the A80 featured one of the finest mechanical transports in existence. The transport was rugged and stable, yet extremely gentle with tape. The tube-era C37 and J37 that preceded the Studer A80 already had quite a reputation, but the A80 with its superior transport rightfully earned its place in many of the world’s finest recording and mastering facilities. The A80 featured solid-state electronics throughout. The control electronics were smartly designed and extremely reliable.

The rear of the A80, with power connector and electronics. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.

The rear of the A80, with power connector and electronics. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.The audio electronics were decent-sounding and were certainly of professional quality, and also reliable. The electronics came in the form of boards that could be easily plugged and unplugged for maintenance. Calibration was accomplished by means of readily-accessible trim pots, using a screwdriver.

The amplifier cards of the Studer A80. The holes are for inserting a screwdriver to adjust the trim pots. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.

The machine was heavily constructed on a massive frame that held the three motors and various other components. The assembly was mounted on a trolley, which allowed the heavy machine to be easily wheeled around.

The transport featured two tensioners that are unmistakable to the A80, which were symmetrically arranged left and right, each with two bearing roller turrets.

The unmistakable tensioners of the Studer A80. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.

The unmistakable tensioners of the Studer A80. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.The tape head block was massive and contained the erase, record and reproducing heads of the required format. Some A80s had a meter bridge, while other versions didn’t.

The Studer A80 head block, edit switch and stereo/mono switch. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.

The Studer A80 head block, edit switch and stereo/mono switch. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.The A80 was widely adopted by recording studios, broadcasting facilities and even disk mastering houses, as it was one of the very few tape machines offered in a special “preview” version, which provided control signals to the pitch and depth control electronics of a disk mastering lathe.

The preview head version of the Studer A80, here in 1/4-inch format. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold, Salt Mastering.

The preview head version of the Studer A80, here in 1/4-inch format. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold, Salt Mastering. Studer A80 preview head machine in action. The 1/4-inch stereo configuration was what one would normally purchase from the factory, back in the day. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold.

Studer A80 preview head machine in action. The 1/4-inch stereo configuration was what one would normally purchase from the factory, back in the day. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold. The Neumann VMS 66 lathe and the 1/2-inch Studer A80 preview head tape machine at Salt Mastering. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold.

The Neumann VMS 66 lathe and the 1/2-inch Studer A80 preview head tape machine at Salt Mastering. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold. The additional rollers forming the tape path of the 1/2” preview head A80 machine. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold.

The additional rollers forming the tape path of the 1/2” preview head A80 machine. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold.

This setup allows him to cut lacquer masters from 1-inch stereo tape, all-analog, while still utilizing the pitch and depth automation system of his VMS66 lathe! But I’ll let Paul tell you more about his A80 machines.

J.I. Agnew: Where did your A80 machines come from?

Paul Gold: Soon after I got my first [disk cutting] lathe in 2000 I decided I wanted to set up an all-analog cutting chain. I had my work cut out for me learning cutting, so it went on the back burner for a while. In about 2005 I had cut a bunch of sides for another mastering studio that had sold their lathe. They were taking a long time to pay [for my work]. I knew they had a Studer A80VU preview deck. I said I would take it in trade [instead of payment]. This deck became the 1/2-inch deck I use now. It originally came with both 1/4-inch and 1/2-inch heads and rollers.

The next machine came from [the former] Sony Studios in New York City. They had an auction when they closed, and I picked up a complete 1/4-inch A80VU preview deck and another partial deck for parts. By this time it had become apparent that changing over the deck from 1/4-inch to 1/2-inch was less than ideal. To get the best performance out of the decks, they needed to be set up for the tape width they would play.

Enter Dan Zellman, who is a factory-trained Studer technician. I had him go over both decks with instructions to make them like new. He restored the electronics and did some judicious upgrades. Nothing too crazy. He put modern low noise op amps in and made a few circuit modifications he had come up with over his decades of experience with these machines. They were mechanically restored as well [with] all new bearings, dash pots and brake bands. The capstan motors were all rebuilt by Athan. The machines really sang after he was done with them. It was then I decided to put together a 1-inch two-track preview deck. It’s the only one in existence as far as I know. There aren’t many 1-inch recording decks around. It is a non-standard format. I figured anyone who went to the trouble of recording to 1-inch tape would probably like the option of an all-analog (master disk) cut. Studer A80 preview head tape machine, in 1/2” configuration. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold.

Studer A80 preview head tape machine, in 1/2” configuration. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold. The tape path of the 1” stereo preview head Studer A80. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold.

The tape path of the 1” stereo preview head Studer A80. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold.

JIA: Quite a process! So how are they performing? PG: I’ve been quite happy with the decks in use. They are very reliable and sound great. I have used other types of tape machines over the years but the Studers stand out. There weren’t many choices for preview decks. I had only ever seen Studer decks in New York mastering studios so I figured those were the ones to get. Besides [their] sound, there are many things to like. They are very reliable. After restoration I’ve had very few problems with them. You turn them on and they work. Parts are still available. There are still factory-trained Studer technicians around for service. The transport is a thing of beauty. It’s extremely gentle with tape, and also forgiving. Other tape machines will hiccup with a sticky splice or poorly-slit tape. The Studers just sail right through it. I handle a lot of historical tapes, so gentle tape handling is a must. I am a technician for the Neumann lathe but I leave the tape machines to either Dan Zellman or Bob Shuster. I don’t know tape transports like they do, so I leave it up to them. I watch and pick up what I can so I can take over when they are no longer available. ****** The versatility of the big tape machines allowed the operator to not only configure their transport in any way they liked, but also to use different audio electronics. Tape machines are very much like turntables in this respect. It is a mechanical transport with a head, and you can hook the head up to any “tape stage” (as in phono stage) you like, even though tape machines typically come with a built-in tape stage. One could use custom tube electronics with an A80 to make a machine that would beat the Studer C37 in every respect. The Studer A80 remained in production until the late 1980s, when the next generation of Studer machines came about, such as the A807. These were smaller, lighter units, in which the screwdriver-adjustable trim pots had been eliminated. Instead, calibration was accomplished via a digital interface with plus and minus buttons, a concept which was to remain until the Studer Group was purchased by Harman International and the company eventually pulled out of the tape market. Many A80 machines are still in regular use around the world. They were sturdy enough that many are still in excellent condition, and parts are still obtainable to restore them and keep them running. Second-hand A80s currently sell for between $7,000 and $14,000 US dollars, depending on version and condition. However, this is only a small fraction of what you would have paid for one in the 1970s, which has enabled many audiophiles to acquire such machines for their home listening systems. Whether for professional or home use, the Studer A80 is quite a bargain in terms of quality for your dollar. It is really a machine for a lifetime and with minimal maintenance, it will give many more years of excellent recordings and listening satisfaction. The A80 is equally popular in the US, Europe and Asia, with good availability of parts and knowledgeable techs in every region. Many recordings are still being made on A80s or mastered from them, over 50 years after their introduction, despite the massive changes in the audio industry. In fact, industry trends are shifting in favor of tape again, and there are even software emulations of the Studer A80 available. (I’d still take the reel thing any day over an emulation!) Seek them out but be warned: prices are currently trending upwards! A closer look at the 1-inch stereo head block and the Sprague repro heads used on Paul Gold’s preview A80. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold.

A closer look at the 1-inch stereo head block and the Sprague repro heads used on Paul Gold’s preview A80. Photo courtesy of Paul Gold. A true piece of industrial machinery, the Studer A80 features an hour meter, logging how many hours it has clocked, for adherence to the maintenance schedule. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.

A true piece of industrial machinery, the Studer A80 features an hour meter, logging how many hours it has clocked, for adherence to the maintenance schedule. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.

The head block of a 1/4-inch Studer A80. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.

The head block of a 1/4-inch Studer A80. Photo courtesy of George Vardis.