In Part One of this interview (Issue 195), Steve and John Seetoo discussed Steve’s beginnings in the mastering world, his mentors, and some of his favorite projects. The interview concludes here.

John Seetoo: You’re almost as well known for your online forum as for your mastering work. How did that community develop?

Steve Hoffman: (laughs) There was a forum that my old company DCC Classics began, basically to answer questions about our releases. That had 700 to 800 hardcore audiophile members. They would ask the questions and they’d get relayed over to me, and I’d answer and they’d type them on there. When that company went belly up and morphed into Audio Fidelity, there was one fan of mine on the forum who said, “Let me create something for you, and we’ll just move everything over there.” I said, “Nobody is going to be interested in this.” And he said, “Trust me.” So he developed my forum. It had nothing to do with me. It was just a fan site. And on day one, we had 500 members, and on day four, we had 5,000 members! And it grew and grew and grew, and it’s been 12 years now. We get millions of hits a week. And everybody knows about it.

It has its upside, but it also has its downside. When someone on there says something like, “I don’t like the new remastering of Sgt. Pepper,” and it’s picked up on the internet? Only because it has my name on top, it’ll read: “Steve Hoffman doesn’t like it” – nothing to do with me, just some guy on my forum. (laughs) So it’s a mixed blessing, but it’s really enabled me to reach out and keep in contact with all of the crazy music lovers out there. Not just audiophiles, but record collectors.

JS: Your fan base, like anything else.

SH: (jokingly) I’m like the God of Sound! – not really!

JS: You’re known to have a fondness for tube electronics and vintage gear. Can you explain the attraction of those? For example, unlike the majority of your peers in the mastering field, you tend to shy away from compressors and prefer to add tube saturation and distortion from analog tube-powered EQs. Why is that, and how are you able to control level disparities without compressors and still get the results you have become renowned for?

SH: You are probably the best interviewer I’ve ever had! I can’t believe it!

JS: Well, thank you!

SH: I’ve been yakking about this stuff since the '80s, and this is the best one ever! Here’s the deal: it happened one day, in 1992. And I remember the day – I was working on this jazz album, and I had my giant solid-state amplifier and my JBL monitors, and what happened was, my fellow engineer, Kevin Gray, had a small pair of McIntosh vacuum tube amplifiers that he had purchased at UCLA Hearing Center. When they went solid-state, they put them in a pile and sold them off for a hundred bucks. And I had seen photographs of the old vacuum tube amps, so I was very curious.

So he loaned me his, and I was playing this one song over and over again on my big solid-state amp, and then decided, “let me just hook in these little small amps; they couldn’t possibly sound any better.” So I hooked them right in, left everything else the same, and oh my god! The musicians! They were right there in the room with me! Nothing else had changed. Just these little old amps with the vacuum tubes in them. And they resurrected the dead! I was so shocked. I just couldn’t believe it. I had these giant amps, and then all of a sudden I had these teeny amps that I could hold one in each of my hands, and it slayed the sound of anything else I’d ever heard. I was shocked. So I asked him, “What’s the magic?” And he said, “vacuum tubes.”

So, in the 1990s, I was a real convert. So I’ve been using vacuum tubes in my work ever since, and it’s really helped; especially it helps on the 1970s – you know, in the old days, in the 1950s and early 1960s, all of the old recording studios used vacuum tubes. When that went away in the late 1960s, the recordings started to become drier; less complex and more flat. So when I add a layer of vacuum tubes in there it sort of brings those old records back to life. So I’m a convert, and I’ll tell the world. Yeah, they run hotter, but the payoff is worth it, completely. That was more than you bargained for with that story, eh?

JS: No, no, that was great! I know people who would agree with you 1,000 percent on that topic. And a lot of them read Copper.

SH: And I know a lot of people who also think I’m totally full of sh*t too! (laughs) But they haven’t heard it. They have to really compare. And none of them ever do. They armchair (quarterback) it; they read the measurements, they read the specs, and think, “that couldn’t possibly sound any better!”

JS: I’ve interviewed Alan Parsons in the past and he loves digital because of the horror stories he had to undergo editing multitrack tape with razor blades just to remove a single note or beat on records like The Dark Side of the Moon. As you have handled remasters of so many iconic records from music history, are there any instances where the original tapes had deteriorated to the point where an out of the box salvage solution was required? I have read in other interviews that you try to avoid digital audio workstations.

SH: You’ve done your homework. Yeah, I’ve done all kinds of crazy things. I’ve never really found an unsalvageable analog tape. I found some that were damaged from operator error when they were rewound, or they snapped the tape or a piece was missing…what I usually do is I get the analog safety, so whatever that little piece is, I just edit it in, right onto the tape. I mean, it’s useless anyway, so you might as well repair it for everybody else.

JS: You physically edit it in?

SH: Absolutely.

JS: You don’t edit it on a digital transfer?

SH: No. Well….once in a great while. When you just have to. But other than that, I like to keep it in analog until the very last moment. There’s my oft-told story of the seven years we waited for the [Jethro Tull] Aqualung master tapes to come from Ian Anderson. And he finally found them in his garage underneath his salmon farm tank! (laughs)

He called me one night – it was the middle of the night, I could hear him on my answering machine (with Scottish brogue:), “Hey this is Ian!” I’m going, “Who’s Ian?” Then I remember – that’s Ian Anderson! I’m scrambling for the phone, and he goes, “Eh? You want tapes? I found ‘em!” (laughs) It’s like seven years later, we’ve been waiting for the analog master tapes for Aqualung.

So he sent them to us in this package, it just arrived at my front door, handwritten package…and everything was fine, except for a giant tape stretch of about two feet where the tape was just unusable during the title song – (hums opening guitar riff) you know that song, “Aqualung,” right?

So we hear the song and the vocal goes, (voice mimicking a record slowing down): “feeling like a deeaaaddd ddduuucccckkk….” (laughs). Oh sh*t. Seven years we waited for this. Seven years. So what are we going to do?

Well, we yak and yak and yak, and I go, “I know what I’m going to do. I’m going to call up the label here in town. They still have their safety copy. And I bet, with a little finagling, it’s going to mask pretty well.” So we got their little safety out, we edited that little part in, we mastered it, we put it back on the safety, which they were not supposed to have anyway, because they had lost the rights, and everything was fine. Only I can hear it, but no one else has ever mentioned it or called to complain about it.

It’s just one of those things. So, we saved that (project from) having to be repaired without a (whispers): digital audio workstation. It was all analog. It’s fun to do that, you know? I’m an expert editor, not to toot my own horn, but like Alan Parsons, I learned [how to] splice tape with a razor blade. So if you can do it that way, there’s really no reason to have to do it any other way.

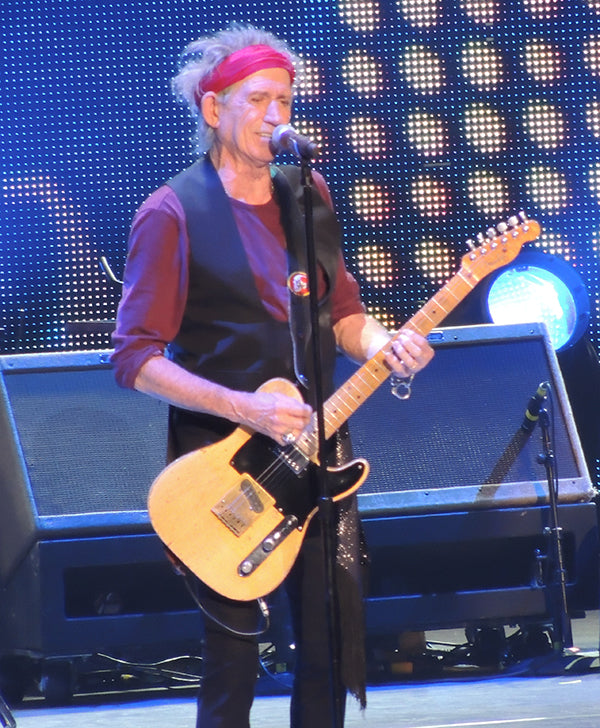

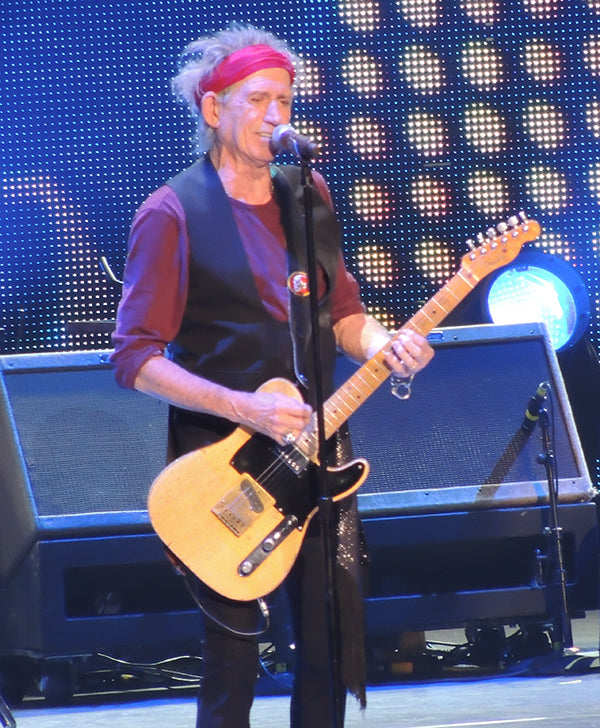

Steve Hoffman.

JS: It’s one of those invisible edits that everyone reading this is now going to look for! There are a number of famous edits, like the guitar harmonics at the beginning of “Roundabout” by Yes.

SH: Or, if you really want to ruin your day, any modern version of “She Loves You” by the Beatles – there’s like eight edits in there! So clearly, it’s like,“oh my god, how could I have not been hearing this as a kid?” So I pulled out my old, worn record of “She Loves You.” I could not hear anything, and that’s when I realized that the echo on there was smearing every sign of the editing! So even back then, they had their own little ways to go about that.

My biggest problem with old tapes is that the (adhesive) paste on the back of the splices dries up over the years and falls off, so every edit that was ever made, and every splice has – died. So we have to repair each one, which is mind-bogglingly time consuming, and – I let my other guys do that, and I just hang around and eat hamburgers. And when that’s all done, we’re ready to go, usually.

JS: It’s a skill that needs to be passed on to the next generation of engineers.

SH: (laughs), Yeah, but it’s not – sadly. And the record companies – they know that. They are now in the process of transferring everything to digital. Transferring their analog tapes all to hi-res. Only problem is, we don’t know what they’re using as their analog source. So, it’s like, they keep offering that to us, and we keep saying, “Look, you’ve already mastered this onto hi-res. We do our own mastering.”

JS: You’ve worked on everything from Bing Crosby, to Johnny Cash, to Coltrane and Miles, to classic rock and Metallica. Do you have any special approaches for mastering different genres of music? For example, do you prepare different protocols to master country music differently than you would for jazz or rock and roll?

SH: Really good question. If there’s a solo instrument, for example – John Coltrane’s saxophone or Creedence – John Fogerty’s vocal – if there’s one instrument that’s supposed to sound lifelike, I work on that instantly. If I can get John Coltrane’s sax to sound like he’s right in the room, I let everything else fall where it may.

One example that I like to explain to people is a lot of these great Creedence Clearwater Revival songs were recorded quite warmly. Not much high end, and the drums sound kind of “thuddy” on them. Most mastering engineers, they hear the sound of the drums and they want to hear the cymbals more, so they turn up the treble when they’re mastering. And that’s all well and good until John Fogerty starts singing and then he sounds like an electronic, I don’t know – amplifier. Not a human being – because his treble is jacked up so much, and he’s already trebly to begin with! So what I do is I make sure that he sounds like a human man, and everything else I ignore, and that drives a lot of other people crazy.

Look, you’ve just bought a Bruce Springsteen album. You didn’t buy the Springsteen drummer album. This is HIS album. You want him to sound like a human being. The drums on “Born to Run” are never going to sound good, no matter what you do, so just give it up. Make sure he sounds like he’s standing there, and then – stop. Don’t do anything else. And that’s how I look at it, no matter what it is – jazz, classical…as long as it sounds like you are there, I’m happy. And if it’s electronic music, then I just want it to sound – pleasing. To me. I mean, pleasing to me. (laughs) I don’t care about anybody else! If it sounds pleasing to me, chances are a lot of audiophiles are going to like it, you know, and a lot of other people.

JS: OK, final question. What’s the best thing that ever happened to you during a mastering project?—whether working with an artist, a particular album, or whatever you’d like to tell us about.

SH: The best thing? Wow, that’s a tough one. You know, I like it when the artist calls me up and, if they’re still alive of course, says, “wow, that’s sounds really great, man.” That I really like a lot. But then the artist goes, “..well, I have some ideas…I’m not really loud enough in this…”

My most personally-satisfying mastering experiences were with the late, great Ray Charles. We worked together for many years, and he was THE guy. He sat there with us and we worked on all of his old catalog, and that was quite rewarding – to be the only guy outside of his circle to sit there and work on “Georgia On My Mind” and “Hit The Road Jack”…so working with Ray, that was really wonderful.

Also, I got to work with Sammy Davis Jr. before he died. You know, they’re so appreciative that someone of a younger generation likes their music, it’s just touching.

I just hope the trend in recording goes back to natural-sounding music – now I sound like an old guy when I say stuff like that! (laughs). But you know, it’s not all about earbuds. These young kids today – they should actually have their own stereos, like we used to in high school and college, so that they can really enjoy the music that they like, but it would make it a lot more enjoyable for them, and it would pass the torch onto other music lovers, who could also become audiophiles.

This article was first published in Issue 37.

Courtesy of Gilles Laferriere/PMA.

Courtesy of Gilles Laferriere/PMA.