C: For whatever it’s worth, there are some markets where physical media, primarily CDs, still dominate…

P: Japan!

C: …Japan and Germany in particular…

P: And Japan’s at the leading edge of technology, it’s wild. Obviously they know something.

C: —Or it could just be a cultural norm that they’re used to.

P: But it was a cultural norm everywhere. It’s changed; why did it not change there?

C: ….It’s a worthwhile question.

P: They are known to be enlightened people. [laughs]

C: [laughs] On the whole, yeah—but there was that whole World War II thing…

P: [laughs]…but they have been known to be philosophically and artistically enlightened people.

C: I understand that…one of the things that dominates discussions in the audio world —other than who went broke this week— is how do get newbies into it? The perception is that guys your age, my age, we’re dying off, are we bringing in new folks to buy stereo equipment, to buy records? Clearly, the records seem to be driving things …

P: The thing that made me most disillusioned at first…and still gives me great pause…is the whole Crosley phenomenon. I stood up in front of a whole coalition of independent record store owners a number of years ago and said, “we need to NOT be doing this. We need to not be a part of this. Don’t be selling these in your stores.Don’t do this, this is bad for us, ultimately. every single person who buys a Crosley is going to get out of this hobby. So…don’t do this.”

I think it impacted a few people, but that part of it is very concerning to me. That’s when you get into the question of “is this a fad?”—when you see people buy a $40 record and put it on a Crosley and pretend like they’re getting some superior experience….no, you’re not. You’re getting a vastly inferior experience.

C: The irony is that the market for used turntables has gone up dramatically, and there are of course halfway-decent low-priced tables like the U-turn….

P: Let’s go back to another part of our conversation: there is a generational shift happening, and people don’t have the space. I built my life around a book collection, a stereo, a record collection, a comic book collection, a chef’s kitchen…I built my life to accommodate these things. These were things of value in the ’50’s and ’60’s. They’re not, anymore. In cultural terms, it’s shifting, pretty big time. In that shift there’s still an appreciation of parts of it, but part of that shift is a dumbing-down of the hardware side of it…which is disillusioning, and I’m sure it’s hair-raising to you guys.

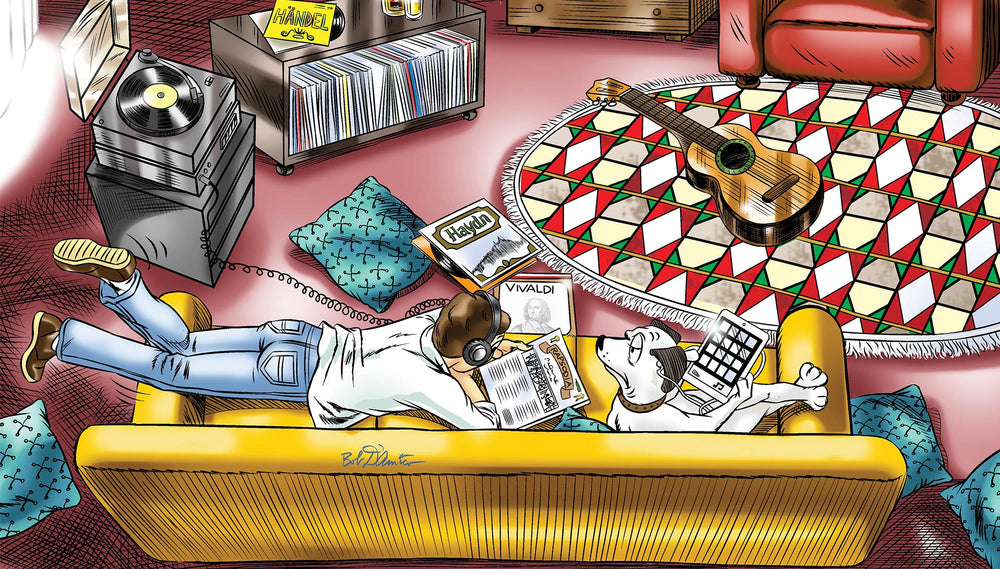

C: There are a lot of people who believe that the headphone phenomenon is going to transition into folks getting back into big-boy stereos. I’m not sure that’s the case, because [headphones] are an isolating experience, at least to me.

P: It is isolating. But the whole shift back to physical media is a good sign, and here’s another good sign, that you may take some hope from. Amazon’ stated goal in the beginning was to end physical retail. The end-game with Amazon seems to be to start opening stores. Think about that for a moment….

C: It’s clear they know more about profits with an “f” than prophets with a “ph”….wow, there’s a book title there.

P: Good one–you should save that, copyright, patent pending….[laughs]

C: Gizmodo, a few years ago…had me writing about high-end audio. The interesting thing to me was…the 600-some comments were nearly all hostile, nearly all said that anyone who spends more than $300 on sound equipment is insane, it all sounds the same…

P: …No, it doesn’t!

C: …I know. But I think the reason that a younger generation might think that is that they’ve grown up with MP3 and earbuds…

P: …and it all sounds horrible. It all sounds horrible. So yes, they do think that. To them, the peak experience of audio is being at a movie. That’s the highest it ever gets for them, being in a movie theater…

C: Ironically, back in the ’30’s and ’40’s, that peak experience may well have been a movie, with the Western Electric, RCA and Altec sound systems….

P: …But now it’s horrendous and loud and just like radio, it’s mixed wrong, and just like concerts, it’s all mixed wrong and all mono, and it’s horrifying. You go to a concert expecting better sound, and it’s like, “Aaaagh! This is TERRIBLE!”

C: I guess I’m turning into an old fart, but it’s very hard for me to go to concerts these days…

P: My line over the last two years in that I’m getting ready to retire from live music. Things keep drawing me, like I’ll go see Dylan at Red Rocks, but it’s so disillusioning. I’m doing it more to be in the room with Dylan, now, it has nothing to do with any kind of quality experience. I’m going to be in a room with other like-minded people of my generation, trying to feel what I used to feel…but it has very little to do with the musical sound quality experience.

C: I think that’s another reason why independent artists have revived the idea of house concerts…

P: House concerts, playing acoustic, playing small venues, that’s a big deal, and that’s a GREAT trend. It’s not just kids and it’s not just old farts who are buying records. Another big segment of our audience is…every single day at “Band O’Clock”, which is about 2:30, they all come in. Whoever’s playing at the Ogden, Bluebird, Fillmore, Pepsi [local concert venues]—they all come in. They want to see their records, they want to see their friends’ records, take a picture of it…they are still into the physical. In the early days of this, I was furious that none of these assholes…none of the HUGE major stars at the time said, “hey, kids–don’t download, buy a record, it’s much better. If ANY of those guys had said it—the only one who did was Lars Ulrich [of Metallica], and he got crucified for it—if ANY of these guys had had the balls to say it… but none of them were willing to put their career on the line and say. “this music sucks, buy a record”…

C: I thought it was amusing that Pearl Jam bothered to sue Ticketmaster [about high processing fees] and now the last time I went to buy tickets, I was dissuaded not by just the cost of the ticket, but by the fact that there was a $16 processing fee per ticket on tickets that I print myself….

P: Well, it’s pretty hard to beat The Man. No matter who you are. [laughs]

C: Now you really sound ’68! [laughs]

P: Yep. Pretty hard to beat the man. But within the walls of my universe, we’re pretty Man-free around here. So I feel like we’ve held onto the artistic goal that the music is important, that the format you listen to is important, and the stereo you listen to it on is important. It’s all important, it’s not just trivial. This is art. This is culture, and we do believe in it. That’s why we’re still here.

C: I think that as we become more and more detached from physical objects and we move into smaller and smaller places simply because we can’t afford anything else, the physical becomes more important, items become little touchstones, or icons…

P: Right. It may be all we have, a few little things in the future that we can hold on to and point to as what we once were, what a great society we once were.

C: Do you see any overwhelming or major cultural trends coming out of the vinyl revival, other than just the vinyl revival?

P: At first it seemed like they were just taking the digital file as it existed, that they made the CD out of, and slapping it on to a piece of wax. I think they’re slowly starting to break out the white lab coats and start to take this like a science again, start to paying some attention to things. One can’t help but think about it with the death of Rudy Van Gelder, that this is both an art and a science, making records, and there is some attention being paid.

Certainly, [these days] the sound of CDs and surround CDs and Blu-Rays—the sound is astoundingly good. After years of ripping people off, CDs are fairly priced and they actually contain some great sound, on some of them. Records are starting to be pressed and recorded correctly, in some cases, again. Some audiophile ones rival anything I’ve heard from the ’50’s—my standards are gonna be an original mono Blue Note on my VPI through my Everest speakers—it’s gonna be a profound experience, that’s my standard—and so there are some things that are impressing me, coming out now.