After the last two issues’ litanies of sins, by both the tape manufacturers and the end users (but not the vendors), I tried to place myself back in the 1950s and 1960s to assess whether or not I was being too harsh. If anything, I was too soft on these hi-fi offenders. As Copper is and must remain apolitical, I am loath to discuss it in the following terms, which will upset Millennials, snowflakes, Gen-Xers, and others, but I must do so for context. It’s all about the blend of education, intelligence and comportment, then vs now.

It’s clear to me that the audiophiles of 60 – 70 years ago were far better-educated and savvier than we are today. This is why the mishandling of tapes (which I confess is just about as minor a malfeasance as one could possibly imagine during a time when the planet is dealing with war and pestilence) is so surprising. But each time I start to resemble my old man, exhibiting the grumpiness of age, I stop myself and admit that there’s absolutely no reason why any generation needs to know how to use the tools, appliances or other appurtenances of decades past.

It’s like that YouTube clip in which some children are handed cassettes and a boombox, to try and figure out how it works. They’re mystified. I imagine there are young drivers who couldn’t handle a manual gearbox, and I wouldn’t know how to use a spinning wheel, so why should anyone under 40 be versed in the use of open-reel tape, let alone vinyl?

Again, this isn’t the place to discuss the degradation of basic education in the US and the UK (and for evidence, just look once more to YouTube for some videos that ask a series of questions recently asked of university students to see how depressingly dense some have become). Neither is this the platform for bemoaning poorer manners, attitudes of entitlement, susceptibility to triggers and so on, but simply flipping through some yellowing hi-fi magazines from 1953 through 1954 made me realize how easy we have it today. Everything in the modern world seems to conspire to enable sloth.

Our softer lives as audiophiles doesn’t mean only the plummeting in real terms of the cost of hardware, which is now so low as to have devalued hi-fi equipment. You had to have some serious disposable income to indulge in decent audio equipment back in the early days, even at entry-level. Leaving aside the lunatic fringe that is high-end audio circa-2022 with its $12,000 cartridges and $500,000 speakers and $100,000 amps, the entry-level is so inexpensive today that the once-basic UK system of the late-1970s and through the whole of the 1980s, which sold for around £500/$700 in old money, costs the same today. Yes, £500 will still buy a basic set-up.

Unbelievable? A fantasy? No: you can still purchase a CD player or turntable, a budget integrated amp and a pair of two-way speakers for that sum. If inflation had hit hi-fi, today’s $700 system should cost around $2,200. So, if a hi-fi system costs less than an iPhone, there’s no wonder it holds no more desirability than a toaster. But I digress.

Early audiophiles without deep pockets – and I’m getting to the role of open-reel tape during the birth of serious hi-fi – were a hardy bunch. If you couldn’t afford McIntosh or Fisher or Harman/Kardon gear, you saved a bundle by building it yourself. Do-it-yourself was one way of dealing with the relative exclusivity of what was then the high-end, and it’s why Dynaco, Heathkit and others were so successful. What it also suggests is that those who assembled component systems in the 1950s were a tougher breed than customers for all-in-one consoles.

What I detected, three generations on, were various behavioral schisms. The DIY guys and well-to-do audiophiles (who could buy McIntosh, et al) probably respected their tapes and LPs a bit more than those who bought what was effectively a piece of furniture, one that happened to house a record changer. In a sense, that’s true today: hard-core audiophiles are the polar opposite of B&O customers, or newcomers to LPs who (as I described before) run back to the record stores where they paid $25 for the new Ed Sheeran album to complain about how it skips, after they subjected it to a nasty $99 turntable bought online, while handling records like they were Frisbees.

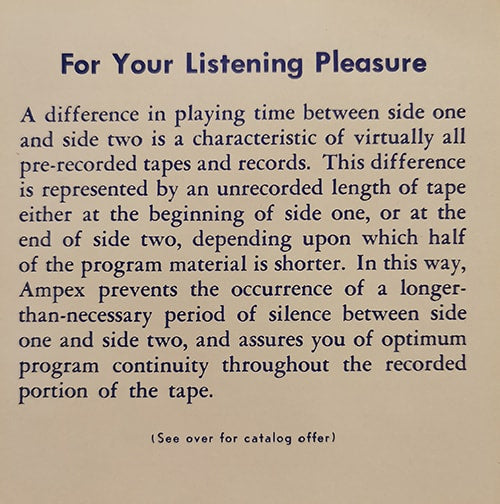

One change between the music providers of open-reel tapes and LPs in the 1950s and 1960s and the labels today is in communication with the end-user. British label EMI in particular was noteworthy for its LP inner sleeves that included densely-packed information about handling and cleaning records. As for open-reel tapes, I’ve photographed for you one of the slips of paper that were found in tapes with unequal playing times from Side A to Side B. In plain English, an even more succinct note says (and I quote verbatim), “NOTICE: On some pre-recorded tapes there is more music on one side and consequently, an unrecorded length of tape on the other side. This is not a defect, but is unavoidable on 4-track tape.” Clear, simple, and informative – as it should be.

A courteous note explaining the differences in playing times from A-Side to B-Side.

Anyone rushing back to the music store to complain about relative playing times could only be a cretin. And, yes, there were tight-fisted cretins who filled those longueurs with extra music because they couldn’t bear the silence. But what I have yet to see on any of the tape boxes are warnings about keeping the tapes away from magnets, e.g., not leaving them on top of loudspeakers, or about proper spooling and so on, which leads me to another supposition: that buyers of tapes, for the most part, simply knew how to use them. That must be the only explanation, especially vis-à-vis veteran vs newly-converted LP users. We simply knew how to handle records. Some newer listeners don’t, and weren’t shown how.

Then again, it wasn’t all savvy audiophiles back then, either. While writing this, I have experienced three tapes in a row suffering the sins of the fathers. (See my article in Issue 160.) The original owner, and I use the singular as all came from the same source, clearly cared not about the health of his tapes. The minor problem with one tape was that the A side and B side were reversed, but another tape required three splices, and the third was so worn that it exhibited a wavy edge and produced so much wow as to be unlistenable. The tragedy is that the last one cited is a super-rare tape, but encountering disappointments like this comes with the territory. As for context, regarding this brazen carelessness and disregard for value, the price stickers on these circa-1965 titles say $7.95 apiece. That’s $72.56 in today’s money, down the drain. Hmmm…no respect.

Negativism aside, such niceties as the warning notes about playing times are part of the charm of pre-recorded reel-to-reel tapes, and seeing them so many years after their mass-market demise. (Please don’t take that as a dig at the current purveyors of 15 ips 1/2-track tapes, but as desirable as they are, $500 tapes hardly constitute what you would call anything beyond “niche” – and a minuscule one at that.) Individual labels such as Command and Audio Fidelity would regale you with scrupulous details about the recording sessions and the hardware used, especially microphones and tape decks, information now rarely found unless your LPs are from Impex, Mobile Fidelity, Analogue Productions and the like, or SACDs from Octave, MoFi and the Japanese specialists.

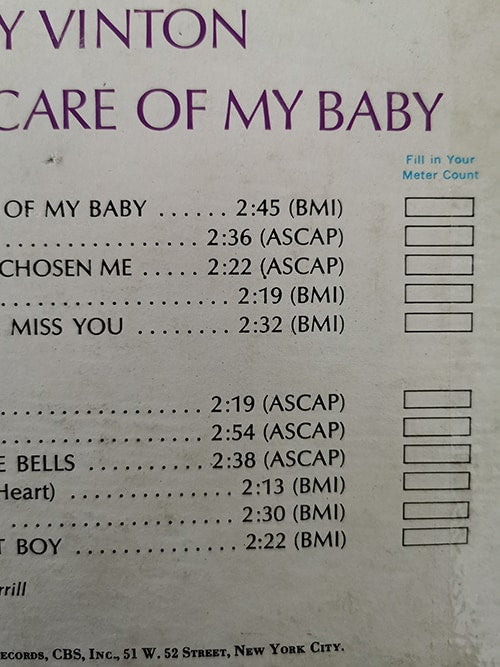

A thoughtful example of a courtesy from a mainstream label clearly acknowledging that its customers might be fastidious appeared on the back of a Bobby Vinton tape. Vinton – now 87! – is a crooner who had numerous hits in the 1960s, but his albums were hardly what I would have thought were audiophile fare like Miles Davis or Dave Brubeck or Leonard Bernstein titles. (Hey – I’m not the snob; I’m the philistine. I’m just saying.) Anyway, on the back of the Vinton release was an invitation to “Fill In Your Meter Count.” A small box was printed next to each track for that purpose. A nice touch, clearly not applicable to CDs or LPs, but charming nonetheless.

Fill in your meter count for easy song access.

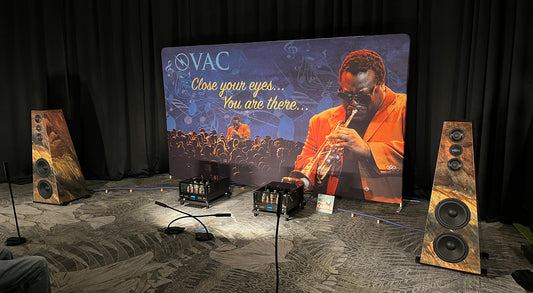

Such discoveries have entertained me from the first delivery of a batch of tapes five years ago, upon my return to the open-reel fold. Again, my library may be too small to serve as a valid sample, but I have – not counting duplicates – managed to assemble by accident a nice collection of tapes which will serve me well if I ever hit the road again, undertaking demos at hi-fi shows.

Just before COVID-19 gave us a glimpse of the apocalypse in late 2019, I gave demonstrations of early pre-recorded open-reel tapes to packed rooms at the Hi-Fi News-organized show at Royal Ascot in the UK. These were hardcore audio enthusiasts, the majority of whom hadn’t really experienced reel-to-reel tape. A couple of late-1950s 2-track 7-1/2 ips tapes caused jaws to drop. This made it all worthwhile, vindication for my obsession with and proselytizing about the format.

Thanks to my omnivorous attitude toward used tapes, with a total lack of discretion or selectivity when shopping, I now have a number of titles that were issued in both 3-3/4 ips and 7-1/2 ips 1/4-track. These will prove invaluable for comparing the two speeds for curious audiences. Attendees will certainly hear the difference, but I’m dying to know if they find the doubling of the speed subtle or mind-boggling.

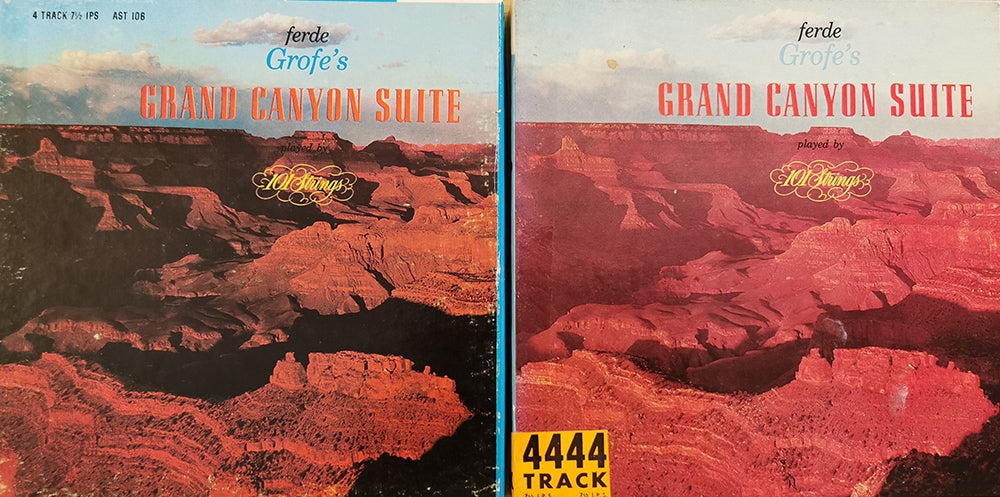

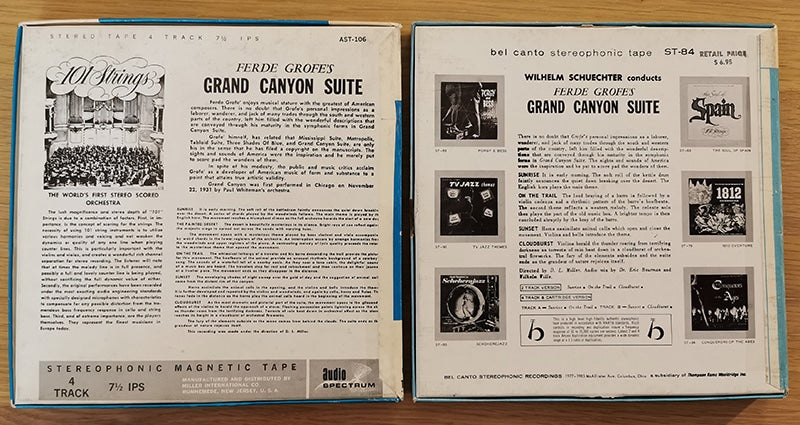

Less obvious will be comparing reissues of the same tapes on two different labels. As I dig deeper into this – and I would give anything to have an hour or two with the late Mel Schilling or Tim de Paravicini to discuss it – I will try to regale you with information about forgotten labels. For the time being, check out the photos of two copies of 101 Strings’ version of Grofe’s Grand Canyon Suite. One is on Audio Spectrum, the other Bel Canto, both 7-1/2 ips 1/4-track, and (blessedly) both mint. The cover art is identical, the spools different, the backs sporting liner notes unique to each.

The same recording on two different labels, Audio Spectrum and Bel Canto, back covers.

The same recording on two different tapes, Bel Canto and Audio Spectrum.

This is the sort of pairing I will gladly take to the next hi-fi show, the team in the open-reel room charged with setting up two identical decks, as they did in 2019. It’s the kind of experience which I savor the most in the hi-fi community, something lacking since high-end audio became so serious. In simple terms, it’s about having fun.

Header image: Ferde Grofe’s Grand Canyon Suite reel-to-reel tapes on Audio Spectrum and Bel Canto, front covers.