At this point in our lathe appreciation journey, I feel I should invite you to have a seat on one of my specially-designed lathe appreciation chairs, complete with straps and other gadgets, and present to you what I consider to be the “poetry” of the disk mastering lathe world.

Affectionately known as the “bathtub” Scully lathe, the Model 501 (see header image), later revised to the 601, was the longest-running Scully model, and in fact the longest-running disk recording and mastering lathe model in the entire industry. It also had the longest-lasting lathe bed design, even exceeding the Neumann lathe bed lifespan, which had remained in production with only minor changes from 1931 to 1979 (from the AM31 to the VMS70).

John Scully was born in 1839, so for much of his early life, sound recording simply wasn’t a thing. He began making disk recording lathes around the late 1910s, in the acoustic era of sound recording. His machines were cutting grooves in wax and instead of a cutter head (in the electrical recording sense of the term), they had a sound box, connected to a large horn, into which the performers had to scream… erm, sorry, I meant perform. Due to the size and weight of the assembly, it was not practical to move it over the surface of the wax disk, so in those early days, it was the platter that moved under a stationary sound box. This setup lasted up until 1925 and this is where the humble beginnings of electrical recording can be traced.

The first electrical Scully lathes started appearing in the mid-1920s and remained very much the same up until the introduction of the LS-76 in 1976. (See Part Six of this series in Issue 156) for a thorough description of the LS-76.)

There were two basic models, the 501 and the 601. The mechanical design of the machines was very similar, with minor upgrades and changes over time. What did remain unchanged from around 1925 up until 1976 was the lathe bed shape, the belt-driven platter with a flywheel under the bed, the railroad-track slide system for the carriage, the massive and instantly recognizable carriage arm, and the level of craftsmanship that went into making these lathes.

The 501 had a mechanical gear shifter on the lathe bed, to set the groove pitch. The system was driven from the same motor that drove the platter, by means of another belt. The bed had two leadscrews, one for records that were cut with the groove running from the outside-in, and one for records with the groove going inside-out!

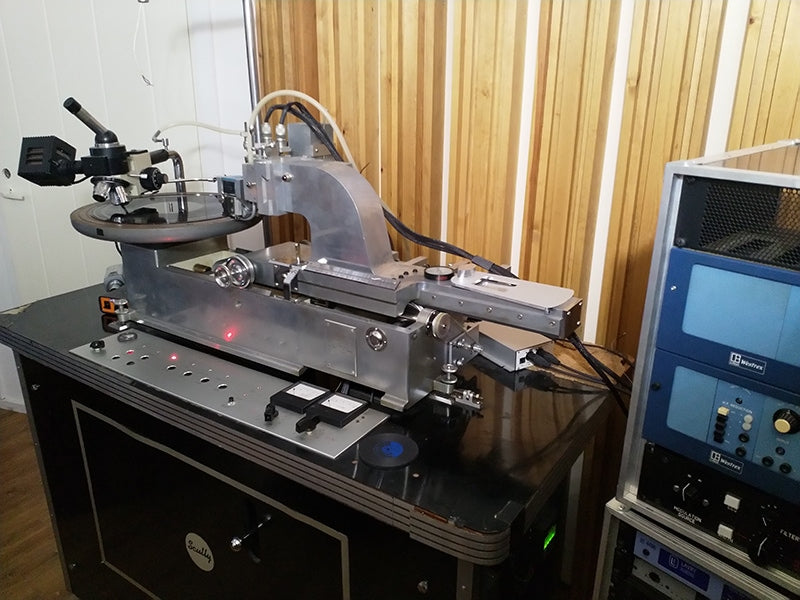

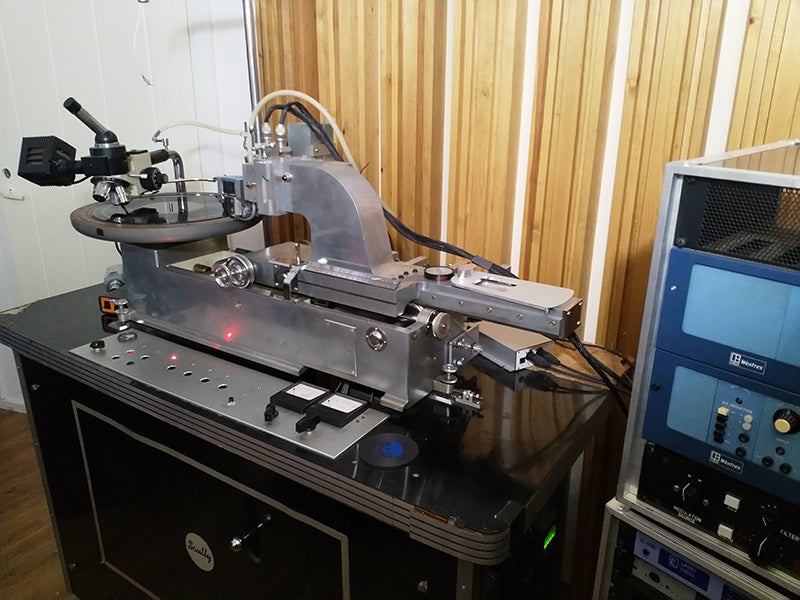

An Agnew Analog vacuum platter on the Scully lathe at Independent Mastering, Nashville, Tennessee. It has a sub-platter with adjusters for leveling the platter, also made by Agnew Analog. Courtesy of Eric Conn.

There were a few variations of the platter-bearing unit over the years, ranging from a Kingsbury bearing with an oil coupler to a much simpler plain bronze bearing unit, adjustable for wear, with a complex arrangement of hollow shafting with an internal shaft for additional decoupling of the platter. The plain bronze bearing proved satisfactory enough to be carried over to the LS-76, in an even simpler, non-adjustable form.

Platters also varied from a plain cork-covered platter, to a cork-covered platter with vacuum ports (for holding the record down through vacuum suction), and eventually an all-metal vacuum platter made of cast aluminum.

The 601, introduced in the 1950s, no longer had the mechanical gear shifter on the side of the lathe bed, but instead featured electronically-variable pitch, with a control panel mounted on the bench of the lathe. Aftermarket pitch automation systems that could be easily fitted to the Scully 601 appeared later. One of the most popular units was made by Capps, a company that was already established in this industry for manufacturing disk recording styli.

A Scully 601 lathe, with electronically-variable pitch from the factory, controlled from the panel on the bench. Courtesy of Jaakko Viitalähde, Virtalähde Mastering, Kuhmoinen, Finland.

Lacquer disks were invented by Pyral in 1931, so the earlier Scully lathes were all originally set up to cut wax blanks. Wax blanks were much thicker and were shaved flat before use. They could be reused by shaving off the old recording, and exposing a flat surface to cut a new recording on. Post-1931, Scully lathes were set up to cut lacquer blanks.

In the late 1950s, the twin-leadscrew era came to an end, so the later Scully lathes came with a single leadscrew. By that point, reversing the leadscrew had become a much simpler affair, so it was deemed preferable to manufacturing two of them! (Believe it or not, some inside-out-grooved records were still being cut at this point in time.)

Scully lathes were particularly large and heavy, with a distinctive industrial look to them. The vertical adjustment of the suspension unit height was accomplished by means of a ball-crank handle, typically found on industrial machine tools of the time. All Scully lathes, from the earliest all the way to the LS-76, were belt-driven. The 501 and 601 were powered by a synchronous AC motor, running much faster than the platter and employing a drive reduction system to deliver the desired record-cutting speed to the platter.

The motors were fitted inside a heavy casting that looked like an inverted bathtub, which was located on the floor under the lathe, and isolated from the lathe proper, with only the belt connecting the two assemblies together. On the lathe side, the belt was wrapped around the large flywheel, hidden under the bench.

Belt-driven platters were very rare in the disk recording world, especially if one compares to the popularity of belt-drive turntables for consumer use. Many disk recording lathes were idler-wheel-driven, some were gear-driven, very few were belt-driven, and even fewer used a direct-drive motor.

Considerably more torque is required when cutting a record compared to just playing it back, and the belt-drive implementations commonly encountered in playback turntables are not designed for the high-torque transfer needed for record cutting.

The Scully belt-drive system was by far the most heavy-duty setup out there as far as belt-driven platters go, but it was still seen by many to be a weakness, especially after the direct-driven Neumann lathes started gaining ground in the US from the mid-1960s onwards.

Many Scully lathes were eventually converted to direct-drive, some even using the same Lyrec SM-8 direct-drive motor found under Neumann lathes. Other Scully lathes also had platter upgrades. David Manley of Vacuum Tube Logic, and later Manley Laboratories, was perhaps the first person to fit a Neumann vacuum platter on a Scully lathe. Others were to follow, but as these vacuum platters were in short supply (they were only available together with a complete Neumann lathe, and not as separate items), it wasn’t until much later, when the CD happened and many decided to scrap their lathes, resulting in a greater availability of parts, that such conversions were possible on a larger scale.

The original Scully suspension unit was designed to carry the Westrex cutter heads and set the depth of cut by means of an advance ball unit (for a detailed explanation of what an advance ball is, what it does, and how it compares to other methods of depth setting in disk recording, please refer to my article in Issue 162). However, it was a simple matter to fit other cutter heads by means of a suitable adapter, or to even replace the suspension unit entirely with anything else one may have preferred to use, as there was plenty of space available with the generous dimensions of the Scully lathe. HAECO (Holzer Audio Engineering Company, founded by Howard Holzer) made their own suspension units that could take Westrex and HAECO cutter heads, and there were the A&M suspension units that were also designed to float the Westrex 3D cutter head. Even Neumann suspension units have been successfully fitted to Scully lathes, often used with Neumann or Ortofon stereophonic cutter heads.

A Scully 601 lathe, with a Westrex 3D cutter head with an advance ball, as originally supplied, and the Westrex cutting amplifier rack next to it. Note the absence of the mechanical shifter on the lathe bed and the presence of a control panel in front of the lathe. Other than that, the lathe bed and mechanical assembly was the same as the 501. Courtesy of Jaakko Viitalähde.

One of the benefits of the design and dimensions of the Scully lathe was that it could be infinitely modified and upgraded. Considering that even in stock form, Scully lathes were among the crème de la crème of disk recording lathes, this often resulted in hot-rodded performance machines, capable of extremely impressive results.

In the monophonic era and up until the 1960s, Scully lathes were the most popular machines used in disk mastering facilities around the US. From the introduction of the “bathtub” Scully up until 1976, approximately 300 to 350 machines were made over a span of over 50 years, which works out to around six machines per year, although sales were most probably not that consistent from year to year. Most Scully lathes were equipped with Westrex cutter heads and cutting amplifier electronics.

The usual Bell Laboratories/Western Electric (a Bell subsidiary) policy of leasing rather than selling equipment also applied to Westrex disk recording equipment. This was to continue up until 1962. Prior to that, it was not possible to actually own your Westrex cutter head and electronics! They could only be leased from Westrex, who retained ownership. In 1962 and after lengthy legal battles for Bell Labs, major changes occurred. One of the results was that the lease regime came to an end and the users of Western Electric equipment, including theater sound systems, motion picture equipment, telephony equipment and disk recording amplifier racks and cutter heads, were given the opportunity to purchase and own the equipment they had been using.

During the 1960s, Neumann came to dominate the US market, and there were more Neumann than Scully systems used for disk mastering from the 1970s onwards. Scully lathes remained popular in other disk recording applications, associated with the motion picture industry. However, due to Neumann’s policy of selling complete turnkey systems only, and the ease with which a Scully lathe could be extensively modified, Scully lathes remained in active service in disk mastering facilities that preferred to use custom and modified equipment.

As a result, even though Scully lathes were outnumbered by Neumann for most of the stereophonic era, in the audiophile sector, more of these specialized-market records were mastered using highly-modified Scully rather than Neumann lathes. There were of course a few renegades who dared to modify Neumann lathes despite the “das ist verboten” policy of the manufacturer.

In the present day, with all of these manufacturers long gone, pretty much all disk mastering lathes in active service are heavily modified, to keep them running and to help give them a competitive advantage to stand out in a very demanding market, which is currently experiencing impressive growth.

This installment concludes our overview of the mainstream disk mastering lathes, so in the following piece, we will be looking at some obscure machines, as well as present-day developments in this now-booming market.

Header image: an old Scully 501 lathe, with the mechanical shifter on the lathe bed, converted to electronically-variable pitch and depth control, with an A&M suspension unit, a floated Westrex 3D stereophonic cutter head, and an Agnew Analog vacuum platter, along with several other modifications. Courtesy of Eric Conn, Independent Mastering, Nashville, Tennessee.