Perhaps I am one of those increasingly rare birds who never had to learn to love opera. When I was all of 11, my father brought home a deluxe, faux leather-bound 3-LP RCA Victor tribute album to the iconic Italian tenor, Enrico Caruso (1873-1921). When he lowered the ridiculously heavy arm of our Garrard turntable onto the deeply moving sextet from Donizetti’s opera, Lucia di Lammermoor, and Caruso, Galli-Curci, et. al. began to sing, I exclaimed over the six voices projected by our Bozak loudspeakers, “Daddy, I’ve heard that before!”

“Yeah, you broke it when you were 2,” was my father’s reply.

From that day forth, I spent many an afternoon playing those three Caruso LPs over and over. Verily, opera, and specifically the acoustic recordings of Caruso, Galli-Curci, and Tetrazzini singing 19th and early 20th century opera of the suffering Italian sort, was in my blood from the time I was weaned. As I became a teenager, I may have spiced my listening with Elvis Presley, the Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly, Little Richard, and finally Donovan, but I always returned to Caruso.

Nor was I alone in my love of Caruso. My father, who was born and raised on Broome Street, on New York City’s Lower East Side, told me that the day Caruso died, people all over his immigrant neighborhood, in both the Jewish and Italian ghettos, brought their wind-up phonographs to their windows and played Caruso records for hours on end. Everywhere you went, all you could hear was the sound of Caruso singing his heart out.

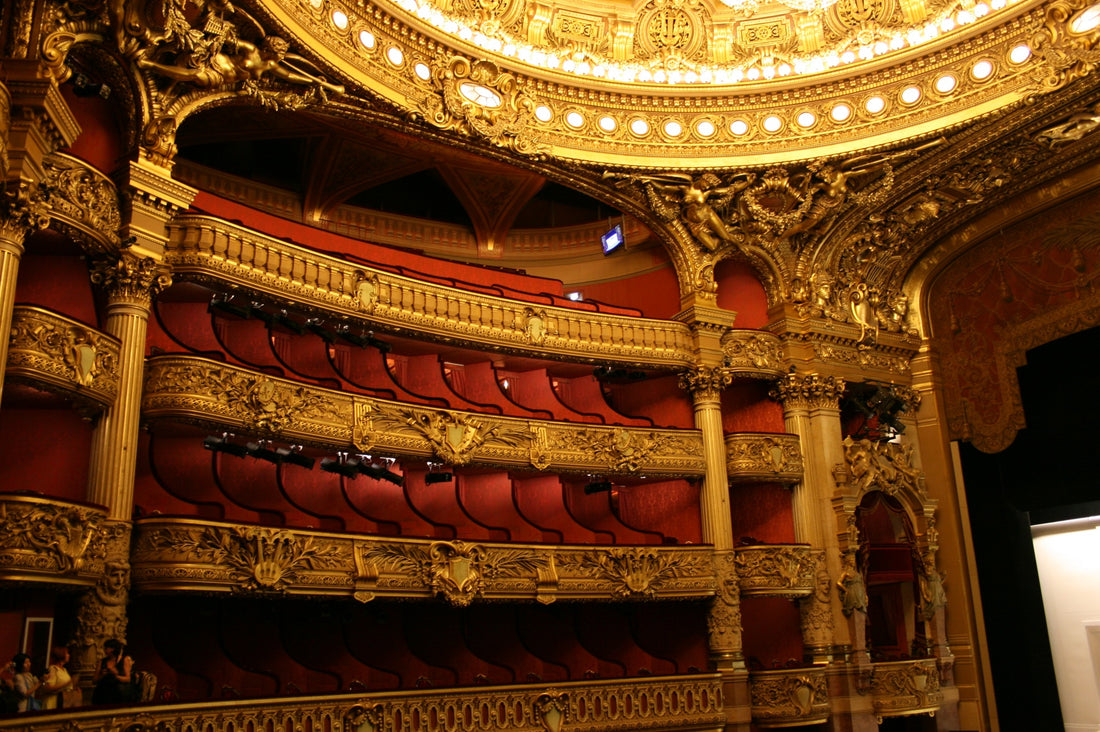

My father also told me that when Caruso sang at the Met (New York’s Metropolitan Opera), he often tended to look up, toward the people in the balconies. All the lower income immigrant standees at the backs of the upper tiers felt that Caruso was singing, not to the rich patrons in the orchestra and boxes below, but rather to them. They loved him all the more for it, and considered him one of their own. In my own way, I did too.

But that was a century ago. For Americans raised on rock ‘n roll, country, pop, hip-hop and the like, the postures, vocal production, and overall conceit of opera may seem strange. Indeed, the carefully trained voices of opera singers are miles apart from the straight tones of pop and jazz artists.

But if operatic vocal production and convention may seem strange to some, imagine how someone from another culture might feel upon discovering, for the first time, a rock guitarist gyrating like crazy and making all kinds of mean faces while strumming and plucking strings and occasionally turning a knob or pushing a pedal. Heavy metal, hip-hop, and the like all have their own performing conventions that are no more natural than high sopranos projecting high E-flats throughout the house. I don’t want to make a big case out of this, but in what way are some of the accents that we’ve come to take for granted from pop singers any more “unnatural” than the carefully enunciated takes on language common to operatic vocalism?

Perhaps it’s unrealistic to expect that most younger readers, or those who do not come from backgrounds steeped in classical music, will immediately take to opera. It is, after all, seen by many Americans – the audience I’m writing for – as a “foreign” art form, in which people in sometimes ridiculous costumes pretend to be kings and queens, heroes and heroines, or various permutations of maidens in distress and the saviors thereof. It is also true that singers sometimes awkwardly move about the stage, flailing their arms and braying like overstuffed bulls on their way to the slaughterhouse. So many of the plots are antiquated, and far too many scenarios ridiculous.

Then again, such a stereotypical description of opera is wildly outdated. A large number of modern productions of older operas attempt to update the scenarios in some way, often by transporting the setting to the 20th and even 21st century. They also tend to favor singers who can act as well as they sing, and look convincing in their roles. Sometimes those updates work, and sometimes they’re unconvincing or preposterous. Nonetheless, it sure makes things juicy when a woman whom a 19th century opera originally consigned to live out her days in a convent instead sings her final aria (song) while turning tricks on a street corner amidst a smattering of empty syringes.

Cultural Relevance

Another prevalent misunderstanding is that all operas are either in Italian, German, French, Russian, Spanish, or some other “foreign” language, and address the events of earlier periods. We now have a large catalogue of contemporary operas in English (and other languages), many of which directly speak to the most pressing issues of our time.

Thanks to recent revivals that have restored music and dialogue that was previously cut, the Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess (1934)

is now accepted as one of the first great American operas to deal with quintessentially American subjects. Two decades later, Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah

Susannah (1955) addressed stultifying intolerance. (Benjamin Britten broached the same subject in Britain with Peter Grimes (1945)).

Gian-Carlo Menotti’s opera, The Consul (1955),

addresses issues that arise when would-be immigrants trying to flee oppressive regimes and run into bureaucratic red tape.

Closer to the present day, America’s John Adams is especially known for his politically-themed operas, among which are Nixon in China (1987),

The Death of Kinghoffer (1991),

and Doctor Atomic (2005).

Other topical English-language operas include Anthony Davis’ The Life and Times of Malcolm X (1986),

Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Anna Nicole (2011),

which follows the comic-tragic rise and fall of model Anna Nicole Smith, and an opera that first made it to New York City this spring, Daniel Schnyder’s Charlie Parker’s Yardbird [see this article and this one as well].

Jake Heggie, who has become one of America’s most successful opera composers, first made his mark with Dead Man Walking.

The opera, which by some accounts is the most frequently performed American opera today, addresses the death penalty in the most heart-wrenching, compassion-inspiring manner imaginable. Audiences are generally reduced to tears at good performances of the work. Another of Heggie’s large scale operas, Moby-Dick (2010), was a huge success. I was so moved at its San Francisco Opera premiere that I attended a second time during the run, and remain convinced of the opera’s greatness.

In the past three months, I’ve reviewed two new politically relevant operas by Americans, both of which lend themselves to fairly intimate chamber settings: the two-act version of Jake Heggie’s Out of Darkness (2016), which deals with the Holocaust – its second act specifically addresses the Nazi oppression of homosexuals – and Gregory Spears’ Fellow Travelers (2015?), which addresses the Lavender Scare of the McCarthy Era in which untold thousands of homosexuals discovered their governmental careers and lives wrecked by McCarthy’s anti-gay witch hunt.

What is Opera?

But perhaps I get ahead of myself. Let’s take a giant step backwards, and do a little Opera 101.

Opera is an art form that melds both sung and instrumental music with text (libretto) in a manner that is hopefully both dramatic and theatrically compelling. Merriam-Webster calls it “a drama set to music and made up of vocal pieces with orchestral accompaniment and orchestral overtures and interludes.” The Cambridge Dictionary, in turn, calls it “a formal play in which all or most of the words are sung, or this type of play generally.”

The definition of opera gets really dicey when you try to distinguish opera from musical theater of the American sort. It’s equally challenging to differentiate European and American operetta (light opera) from full-fledged operas that include spoken as well as sung dialogue (recitative). When Bizet’s ever-popular opera, Carmen, is performed complete, it includes spoken dialogue. Ditto for Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute).

The choice of venue also figures strongly in categorization. George and Ira Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, for example, is considered musical theater in some circles because it premiered on Broadway rather than in an opera house. But when you take into consideration that it had no choice but to premiere on Broadway because its all-Black cast (then called “all-Negro cast”) was not allowed to perform in an opera house, and then examine its overall structure in unabridged form, its identity as an opera becomes clearer. Is Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd musical theater, or is it in fact an opera that got its start in a musical theater context?

Grooving on Opera

Appreciating opera takes some effort. While it’s certainly possible to play excerpts of melodic, 18th and 19th century arias in the background and be touched by their beauty, listening to a complete opera requires far more concentration. Especially if the opera is in a language you do not understand, and the libretto (story) is well thought out and complex, it can be extremely challenging to figure out why people are either singing their hearts out or laughing it up without following the libretto in print or as projected in live performance and video. As for the longer operas of Richard Wagner, or operas that are not strictly tonal, listening without following the words closely is more often than not an invitation to frustration, if not to outright futility and abandonment.

Even before I attended opera, my appreciation for opera and art song grew exponentially as I began to listen to and acquire multiple recordings of the same arias I encountered on that seminal Caruso reissue album. For the first time, I discovered that the accompaniment matters. In fact, in some cases, e.g. Wagner and Strauss, the orchestral accompaniment is as or even more crucial to the musical message as the vocal line.

I also discovered, through listening to recordings and attending live performance, that people performed the same arias very differently. Not only were their voices different, but they also sang at different tempos, and made different interpretive choices as to what words and notes they would emphasize, when to linger or speed up, etc.. Some of these choices, of course, were dictated by conductors or technical limitations, including the length of a 78 record and union rules about overtime. But just as many were determined by the individual temperaments of the singers.

What finally opened opera and art song wide for me was discovering how each voice resonated differently within my being. Some singers made beautiful sounds but left me emotionally uninvolved. Others, including singers who were technically imperfect, touched me so deeply that I went to sleep with their voices in my head, and heard them when I awoke.

For years – decades in fact – I spent hour after hour comparing voices and interpretations on my own. It was only in 1999, when I was first offered the opportunity to write a CD review, that I realized that I had spent a decent part of my teenage and adult years developing my critical listening skills by comparing recodings.

Certainly, it is not necessary to do what I did in order to love opera. Indeed, many people who have season subscriptions to opera companies, and have been attending opera for decades, have never spent time comparing interpretations. They are content with letting the beauty of the music wash over them.

For people with a taste for discovery and adventure, however, listening to the same classic Italian aria performed by sopranos Emmy Destinn, Rosa Ponselle, Claudio Muzio, Maria Callas, Renata Tebaldi, Mirella Freni, Leontyne Price, and Anja Harteros – or, to turn to tenors, Enrico Caruso, Beniamino Gigli, Jussi Björling, Giuseppe di Stefano, Luciano Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo, Piotr Beczała, Josef Calleja, and Jonas Kaufmann – is to discover an oft-astonishing range of musical and emotional expression. The more deeply you explore, the more the emotional and spiritual vistas of opera can open to you.

Throughout this introduction to opera, I link to performances on YouTube. In doing so, I in no way wish to suggest that the sonically compressed files found on YouTube can convey the huge range of color and emotional that singers devote their lives to. Rather, these carefully chosen links will give you a taste of what great singing sounds like. If you’re moved by what you hear, please check out the singers who speak to you via CD, LP, or hi-res downloads.

End, part I